Is all the comforting you’re doing backfiring? Learn about the role accommodation plays in a child’s anxiety.

As a parent, you’d probably do anything to help your child when they’re in distress. It’s kind of our main job as parents: we’re here to provide comfort, offer reassurance, and keep our kids safe. One of the trickiest things about child anxiety is that well-intentioned actions aimed at providing comfort and reassurance often backfire, making anxiety worse in the long run.

If your child has anxiety, you may have already sensed this: the more reassurance you give your child, the more reassurance they seem to need. The more you avoid feared situations, the more their anxiety seems to grow. You’ve unintentionally become the narrator of If You Give a Mouse a Cookie and your child’s anxiety is the insatiably hungry creature who somehow always craves more.

Anxiety therapists have a term for this phenomenon: accommodation. In this guide, we'll explore what accommodation entails, why it's important to address in therapy, and practical strategies for navigating accommodation as parents.

What is Accommodation in Anxiety?

In anxiety therapy, an accommodation refers to any way that you or your family alters your behavior in order to avoid triggering anxiety in your child. This might mean offering extra reassurance, changing your routines, or accompanying your child to activities they used to do alone.

If you’re like me, you are probably used to hearing the word “accomodation” used in a more positive way. Academic accommodations can be a huge help to kids in schools: a child with dyslexia might benefit from getting extra time to complete tests, for example. ADA accommodations make sure that people with disabilities are given equal opportunities in the workplace. These types of accommodations are objectively great!

In the therapy world, unfortunately, accommodation is not so great. While it might provide temporary relief for your child, it tends to make anxiety worse over time. Kids don’t get a chance to learn how to cope with their anxiety, which reinforces their belief that it’s something they can’t manage or control.

Basically, when we accommodate a child’s anxiety, we’re really just enabling the anxiety.

If you’re reading this and kicking yourself for being an anxiety enabler, please don’t. It’s human nature to want to keep someone else from feeling bad. The truth is, we all accommodate our kids sometimes. It’s usually harmless, but for kids with anxiety disorders, it can lead to larger issues.

What are the Risks of Accommodating a Child’s Anxiety?

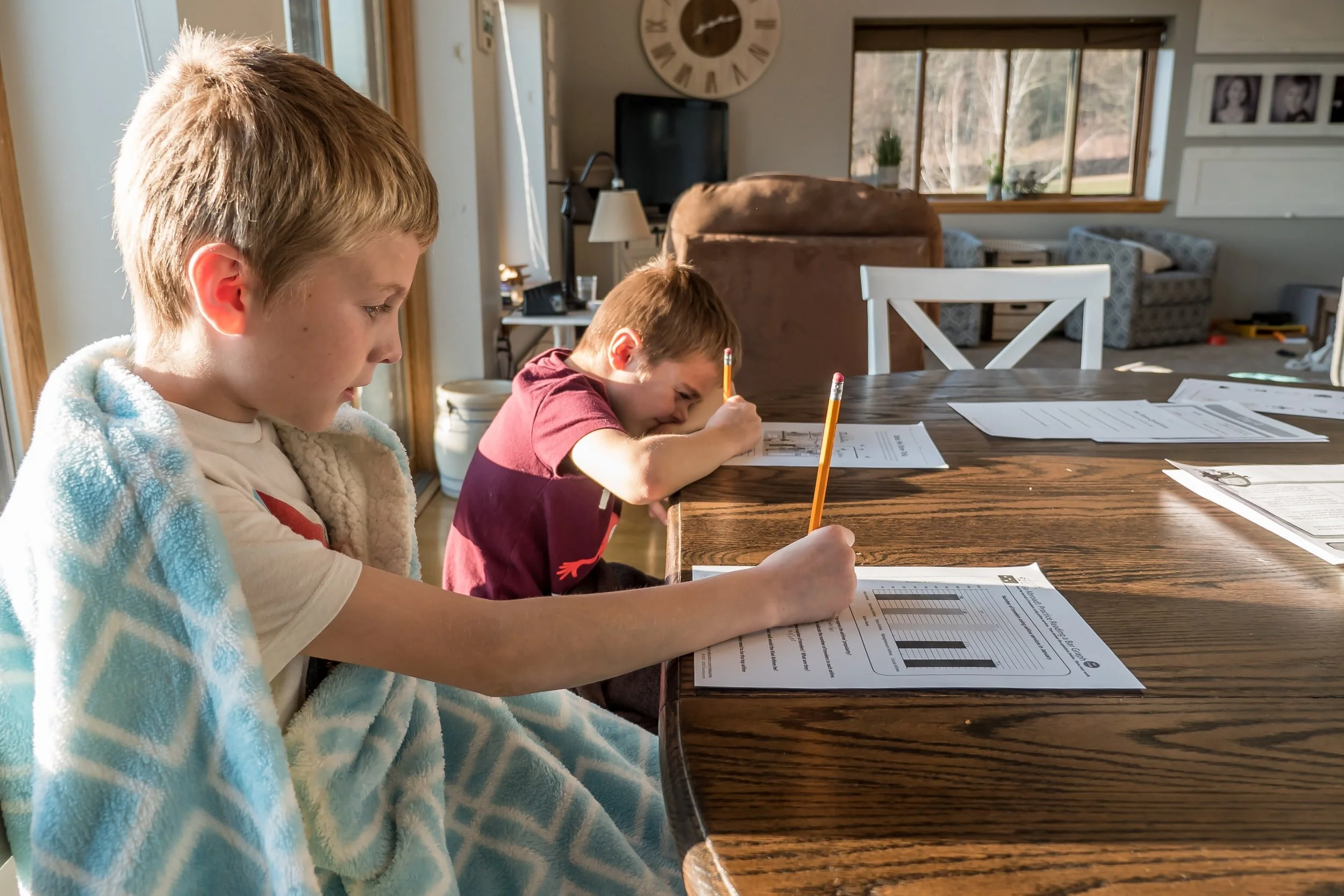

Accommodation risks making anxiety worse over time, leading to more stress for the whole family.

When you accommodate a child’s anxiety, you risk entering a vicious cycle. By giving in to anxiety’s demands, your child misses out on a chance to test whether or not their worries are accurate. Instead, they avoid the situation entirely, which sends the message that maybe this scary thing really is worth staying away from.

This means your child is likely to be even more anxious the next time this scary situation comes up. They’ll need even more accommodation in order to cope. Before you know it, you’re bending over backwards to try to avoid anxious feelings.

An occasional accommodation here and there is a part of life. But repeated accommodation can come with the following risks for anxious kids:

Worsening anxiety

Lack of effective coping skills

Increased reliance on parents to manage anxiety

Disruption to daily routines due to avoidance of triggers

Poor sense of self-efficacy (ability to solve problems independently)

Increased family stress

These risks are much greater if your child suffers from an anxiety disorder, like social anxiety, generalized anxiety, or OCD. These kids’ super-sensitive brains are always looking out for danger, and they’re much more likely to fall into the trap of avoiding scary things.

Examples of Parental Accommodation

Excessive texting is a common and subtle example of accommodation.

So we know accommodation is not great. How can we tell if we’re doing it? While some accommodations are obvious, others are sneaky and subtle. It can be easy to fall into the routine of accommodating anxiety in small ways without even noticing you’re doing it.

Here are some common examples of anxiety accommodation, based on my experience as a children’s therapist:

Allowing a child to skip activities that could trigger separation anxiety, such as field trips.

Driving a child to school to avoid having to ride on the bus or carpool with a friend.

Responding to text messages from the child all day (or all night!) to offer reassurance.

Making sure to always tell you’re child where you are going or what you are doing.

Repeatedly answering anxiety-driven questions, such as “Do you think I’m going to get sick?”

Accompanying a child to activities that peers would attend alone.

Helping a child stay away from triggers, such as crossing the street to avoid a barking dog.

Participating in overly long or rigid bedtime routines.

Changing family routines to help a child remain calm.

Sleeping in a child’s room to avoid bedtime fears.

Keeping special items on hand, such as Purell for a child afraid of germs or a barf bag for a child afraid of vomiting.

If any of these examples of accommodation seem familiar to you, don’t panic! As bothersome as accommodation can be, it’s also incredibly common.

Pretty much every family with an anxious child has some amount of accommodation going on. Therapy can help you scale it back, and empower your child to tackle their fears more directly.

Strategies to Reduce Anxiety Accommodation

Like gradually stepping in to a pool, reducing accommodation is a slow and steady process.

Even if the accommodating is making everyone fairly miserable, you don’t want to needlessly torture your kid. Like it or not, they’re relying on these defense mechanisms to cope. Removing them all at once would be hard on you and even harder on them. Instead, we can gradually reduce our accommodation, which gives kids a chance to adjust, face their fears, and develop healthier coping skills to manage anxiety.

If you want to start gradually reducing anxiety accommodation at home, you can try:

Setting a limit on how many times you’ll reassure your child each day.

Answering anxiety-driven questions only once.

Limiting texting and communication during school hours or after bedtime.

Encouraging your child to try new and challenging things rather than offering a way out.

Making a plan with your child to go to scary places or try scary activities on purpose.

We want anxious kids to learn that they can do things even when they feel scared. Anxiety isn’t something to be avoided: it’s a part of life! Most of the time, their anxiety is just a false alarm, and not an indicator that a situation is really dangerous.

When kids develop this mindset, they can start facing their fears head-on, anxious or not. And, weirdly, the more this happens, the less anxious kids tend to feel. They’ve broken the anxiety-avoidance cycle and taught their brains there’s nothing to be afraid of.

Exposure Therapy for Anxious Kids and Families

Seems simple enough, right? Just…slowly stop doing the stuff you’re doing. But if you’re already way far down the accommodation rabbithole, this is easier said than done. It can feel nearly impossible to course correct if you’ve been answering a million texts a day or sleeping on the floor of your child’s bedroom for six months.

If you find you’re doing tons of accommodating, or your child’s anxiety symptoms are severe, therapy can help. A therapist can help you find creative ways to support your child in gradually facing their fears—without you doing the work for them. If things don’t go as planned, your therapist will help you problem-solve and keep you on track. Their job is to keep everyone feeling challenged, but not burned out.

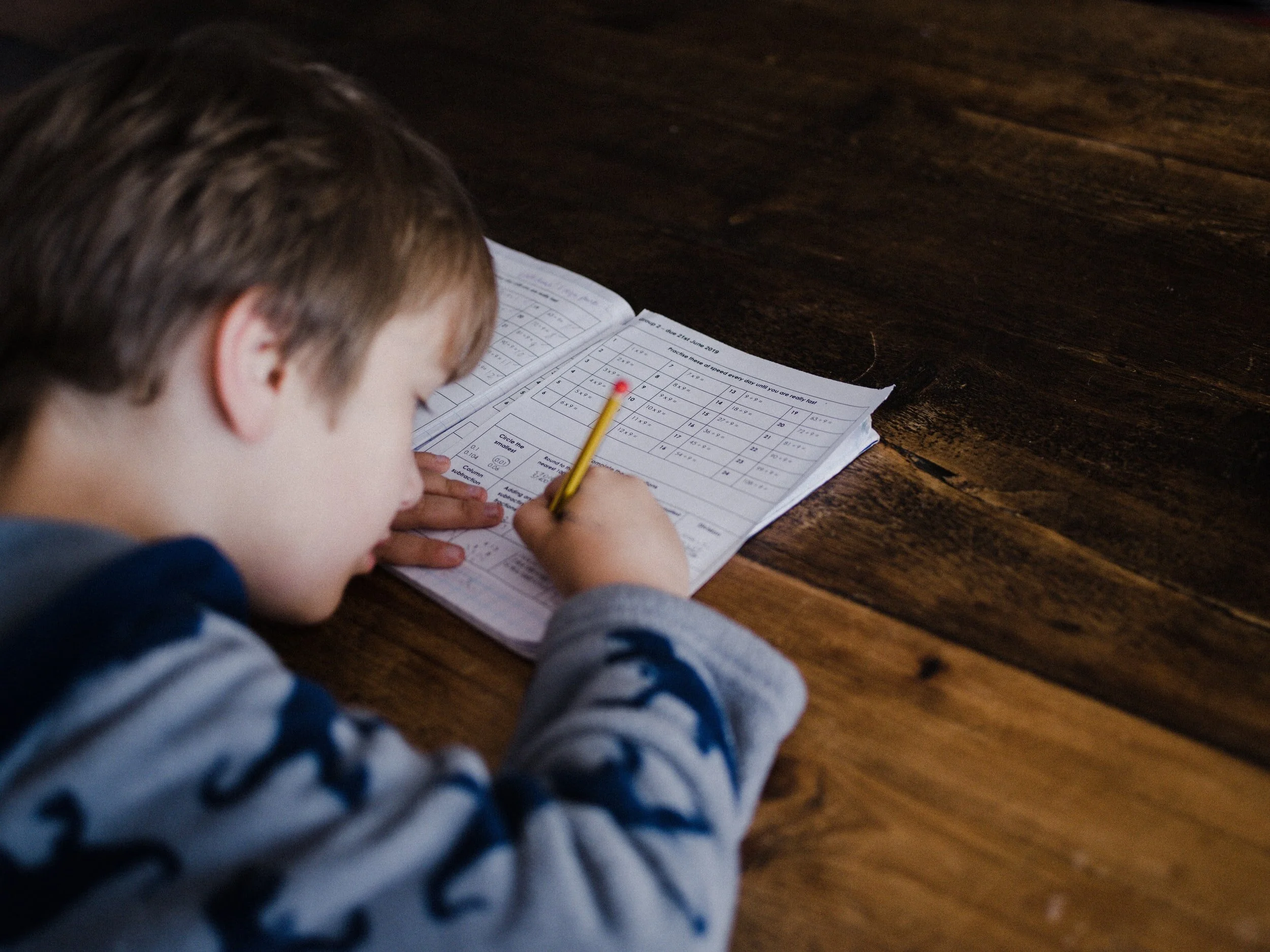

This kind of therapy is called exposure therapy. In OCD treatment, you’ll also hear it called Exposure and Response Prevention. The goal is to help your child take back the parts of her life that anxiety has held hostage, whether that’s sleepovers or field trips or staying home alone. Facing your fears is hard, but a whole childhood without these kinds of activities is even harder.

Therapy for Anxiety Accommodation in North Carolina

Therapy can help anxious kids and teens learn to face their fears and live more confident, independent lives. Photo by Kindel Media via Pexels.

Wondering what could have possibly compelled me to write over 1300 fully original, non-AI-generated words about anxiety accommodation? I’m a children’s therapist specializing in anxiety and OCD. I am lucky enough to help families through exposure therapy on a regular basis, and honestly, I could talk about its benefits all day.

Exposure isn’t right for every family. But if you think it could be the answer to ending accommodation for you and your child, I would love to help! My office is in Davidson, North Carolina (North of Charlotte) but I can practice online therapy throughout the state, and in New York and Florida, as well.

If you don’t live in one of these states, you can search therapist databases for local therapists who practice CBT, exposure therapy, or ERP. These folks will be specifically trained in helping families reduce their accommodation to overcome anxiety.

To summarize, reducing anxiety acommodations helps kids build the skills they need to overcome fears, build resilience, and generally lead more confident lives. If you’re interested in taking the next step, you can contact me here.